Whenever I meet people and tell them I live in Jakarta, there are two things I know they will ask about, the traffic and the air pollution. The traffic is unfortunately inevitable in a city with over 30 million people resident in the greater metropolitan area – one of the largest metro areas in the world. And on some days the air quality is indeed terrible, and you don’t need to look at the AQI (Air Quality Index) app to know the readings are over 200 (“very unhealthy”).

But on other days it’s fine and clear with blue sky, and the difference cannot often be attributed just to changes in traffic volume. A quick google search does not reveal any thoughtful answers to the question – why is Jakarta’s air so bad? Other cities have readily explainable effects driving their pollution problems. Ulaanbaatar in Mongolia is built in a bowl between surrounding hills, and a winter weather inversion locks in fumes from coal fired power stations and the paraffin stoves that many in poorer districts and yurt dwellers still use to cook on. Hong Kong gets smog in the spring when the winds turn and blow from the Pearl River delta area, blowing with it the fumes of Chinese industrial progress. Jakarta is not, however, in a landlocked weather pocket, nor downwind of the biggest industrial area on the planet.

Jakarta’s air has become increasingly polluted over the years, hitting a new low in 2019, when it was named the fifth-most-polluted capital in the world, according to the AirVisual World Air Quality Report. The report found that Jakarta’s air pollution had increased 66 percent over just two years. Indonesia now has the world’s fourth highest mortality rate due to air pollution after China, India, and Pakistan.

In the media, the forest fires that burn across Sumatra and Kalimantan each year are often blamed. It is true that the air quality in Singapore and Malaysia suffers terribly from these fires, but in my experience this does not coincide with the worst air quality in Jakarta. In addition, Sumatra and Kalimantan are both a long way north of Jakarta, and the prevailing winds do not blow in the the right direction for this reason to stack up.

According to the Jakarta Environment Agency, 75% of pollution comes from traffic, 9% from power plants, 8% from industries and manufacturing, and 8% from domestic activities. This list does not include rubbish burning, or construction and road dust, which are also often causes.

Weather

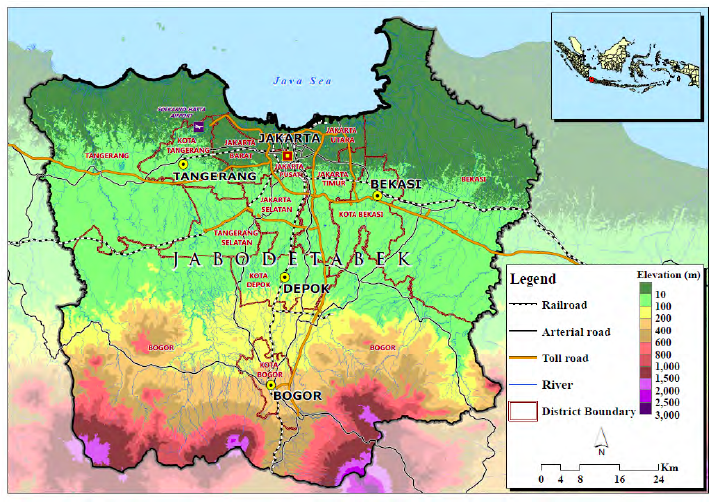

Jakarta air quality is certainly seasonally affected. Jakarta has the Java sea on its north side and the volcanic peaks of several national parks to the south, and near constant tropical temperatures. The wet season, November to March, is dominated by warm and wet northwesterly winds, and usually has clearer skies. The change between wet and dry in April and May is often windy, resulting in beautiful blue skies. The dry season from May to September, with colder, dry south-easterly winds, coincides with the worst conditions, but I can’t find any real explanation of why. Does the dry season create temperature inversions that lock in smog? Perhaps the south-easterlies are blowing across the pollution from West Java, another heavily populated province with over 50million people. Sounds like a good research topic for someone.

COVID skies

The Jakarta Environment Agency reports that the air quality has improved since 23 March 2020 when the city ordered a lockdown as part of COVID-19 emergency measures. We have definitely had an amazing stretch of blue sky days, which is fantastic. Oddly, there have also been a few unhealthy air days, even though traffic flows have reduced considerably, and construction sites are largely silent.

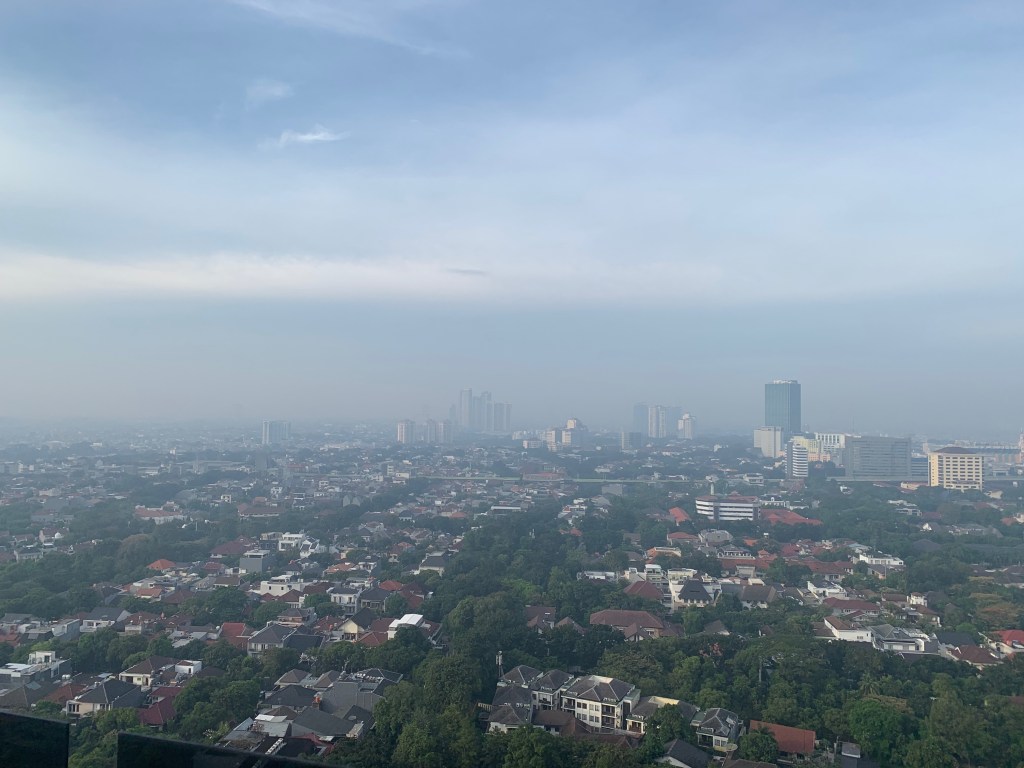

Many commentators are worried that without fundamental redesigns of development, industry, transport and energy activities pollution will quickly return to “normal” and even continue to worsen. The photos show a super clear day on 21 May, 2020 and a day with an AQI of 180 (unhealthy for sensitive groups) on 31 March 2020 – both within the lockdown.

Citizens LawSuit

In 2019 a citizens’ coalition banded together to sue the government over poor air quality. The suit is addressed to the Indonesian President Joko Widodo, and the Ministers of Environment and Forests, Internal Affairs, as well as the Governors of Jakarta, West Java, and Banten (neighbouring provinces that form part of the greater Jakarta area). A similar case was recently successful in Paris, in which the court ruled that the French state had failed to take sufficient action to curb air pollution in the city.

The demands of the citizens’ lawsuit are that the central government issue new legislation that better regulates air pollution, and also that the Jakarta government improve their monitoring of air quality and ensure that this information is shared with the public. The right to clean air is guaranteed by the 1945 Indonesian Constitution, as well as by the 1999 Law on Environmental Protection and Management. While it’s clear that Jakarta’s citizens are becoming increasingly aware of the importance of healthy air, many do not believe the government has a similar concern. The lawsuit, is expected to be appealed by the government and will go to the Supreme Court, likely delaying a final verdict until late 2020.

Traffic Fumes

Jakarta has over 20 million vehicles on the roads, and a large portion of those are motorbikes. Across the whole of Indonesia, motorbikes make up 83% of all vehicles on the roads, third only to China and India in terms of total numbers. The numbers of motorbikes is expected to double by 2030, and the number of cars is expected to grow by over 50%.

To address emissions, the Indonesian government implemented Euro 2 vehicle emission standards for cars and trucks in 2009/2010, and Euro 3 standards for motorbikes in 2013. Euro 4 emission standards have applied to all petrol vehicles since 2018 and will apply to all diesel vehicles beginning in 2021. Euro 5 emission standards, for motorbikes are currently slated for 2023. However, in Indonesia whilst 50% of fuel is imported, 50% is produced locally. Random tests have shown that often locally produced fuel does not meet the required standards. Vehicle standards are not well enforced either with around 50% of vehicles also failing random tests.

Many are calling for early adoption of Euro 5 for motorbikes, introduction of Euro 6 for cars and trucks, along with standards for ultra-low-sulfur fuel. However, introduction of new standards will have limited impact if they are not thoroughly reinforced through testing, and fining offenders. One of the other barriers to adoption of new fuel standards currently is Pertamina’s (the Indonesian state owned oil company) capability and capacity to produce the higher standard fuels.

There are moves afoot to encourage electric vehicle use in the future. In late 2019, I witnessed an electric vehicle rally along Sudirman (Jakarta’s central north-south highway), featuring cars, motorbikes and scooters. Currently electric vehicles are all but non-existent (particularly compared to Hong Kong where being run-over by near silent Tesla’s was a major hazard, and the E-prix was a feature event). PLN, Indonesia’s national power grid operator and biggest power generator, has been tasked to install more charging stations throughout Jakarta, and Hyundai has announced plans to open an e-vehicle factory.

Grab e-scooters surged in popularity during 2019, until an unfortunate fatal accident occurred, since when they have largely disappeared. Electric motorbikes, could become very popular if the number of charging stations increases rapidly, and the if the purchase prices can be kept low enough for Indonesians modest budgets.

Coal-fired Power Stations

Coal-fired power plants still make up 60% of Indonesia’s energy generation. There are seven existing plants and five planned plants, all within 100km of Jakarta. The emissions from the planned new Jakarta area power plants will be equal to adding another 10 million cars on the roads, which is a huge concern.

Indonesia has committed to cut its carbon dioxide emissions as a signatory to the 2015 Paris Agreements. The national target is for 23% renewable power production by 2025, yet in 2019 the actual achieved was only 12%, lower than the 17% target for that year, due to new coal-fired plants coming online. Ten new coal-fired power plants, with a capacity of over 3,000MW came online in Indonesia last year. With coal being a cheap and plentiful in this country which is a major coal exporter, the economic barriers to replacing coal with renewables are not insignificant.

However, there is some hope. In January 2020, the Energy and Mineral Resources Minister pledged that coal-fired plants over 20 years old would be replaced with renewables. This could include up to 69 units of coal, and coal-gas, fired power plants, with a combined power capacity of over 11,000 MW. A new regulation was also announced in March 2020 to ease the development process for private renewable energy generators, and encourage PLN to sign power purchase agreement with them. Coal, however, is still expected to make up the majority of Indonesia’s power mix, at least up until 2028.

Rubbish Burning

Unfortunately, trash burning is still very common in Greater Jakarta where people often burn rubbish despite its harmful effect on both people and the environment and the fact that it is illegal. Experts know that burning rubbish, particularly non-organics including plastic, poses a threat to health and the environment. However unfortunately it seems that many Indonesians do not. Worse still, for many people burning waste is either directly or indirectly, their source of income. Last year tofu makers in the East Java village of Tropodo, were featured in a study by NGO groups. They have long burned waste plastic to fuel their kitchen boilers, and the study found that toxic chemicals, produced from the fires was significantly contaminating the tofu. Some of the waste they were burning was imported from overseas.

There are national and provincial laws and regulations regarding waste management, and environmental protection, which prohibit the burning of rubbish, but this is ignored by many. The laws can impose a jail sentence of a year and a fine up to USD 70,000. Yet a lack of court cases or convictions for waste burning is evidence that either the authorities don’t take the problem seriously, or are under resourced to do anything about.

Aside from enforcement of regulation, the other issue contributing to the problem is a lack public waste collection services. Residents sometimes have to wait 2 weeks or more for rubbish collection, and therefore just burn it. The inefficiency and irregularity of the service seems to be more of a problem than the fee of around US$1 a month, but for some that will also be an incentive to burn.

Greater Jakarta has very few landfill sites, and they are all severely under capacity and poorly managed. Indonesia is second only to China in production of plastic waste, and currently has no public programs for recycling or waste reduction.

The Indonesian government has targeted several cities in Java, including Jakarta, to build waste to energy incineration facilities to tackle the country’s waste crisis. The energy ministry hopes to have 12 waste-to-energy plants online by 2022, generating a combined 234 megawatts of electricity by burning 16,000 tons of waste a day. Environmental groups are concerned that the plants will increase pollution, but if the plants are built with modern technology, operating at very high temperatures and with full exhaust scrubbing systems then this will have to be a big improvement on the current practice of small, scale, open fires, or unmanaged landfills.

Of course the other solution, is to reduce the amount of waste produced in the first place. Indonesia has joined a number of other countries recently in banning the import of waste from other countries, which is a start. However the quantity of waste produced locally is still a huge issue to deal with.

What to do?

It would be lovely if the lockdown blue skies would continue, but that seems unlikely as everyone streams back to work this week. However, if more attention is devoted to changing the old ways, and locking in benefits for the future, maybe Jakarta could overcome its issues. There are many fronts on which Jakarta could make improvements to improve the air quality, particularly addressing traffic fumes, energy generation and waste management.

- Enforcement: Properly police regulations already in place for fuel and vehicle standards, and rubbish burning

- New Standards & Technologies: Introduce new emission standards for fuel and vehicles, and encourage electric vehicles

- Public Awareness: Introduce educational campaigns aimed at energy efficiency, reducing waste, educating on the dangers of burning waste, and encouraging the use of public transport

- Infrastructure: Improve the renewable energy mix in generation capacity. Improve public transport services. Implement proper waste management collection and disposal facilities.

Some of these measures are already in progress, but if they are not implemented quickly it could be too little too late as Jakarta continues its 2019 growth trajectory to being one of the worlds biggest and most polluted cities.